For decades, Libya has existed on the margins of the global art conversation. Isolated by politics, shaped by rupture, and often overlooked even within North Africa, the country has struggled to present a cohesive artistic voice to the world. Yet within this absence lies a quiet truth: Libya’s artistic heritage runs deep, and its contemporary expressions are beginning, however cautiously, to emerge from the shadows.

“Libyan art has never had its moment”, says British-Libyan painter Murad Belhaj, seated in his London studio surrounded by canvases that pulse with light and memory. “It hasn’t been erased, but it’s never really been seen either”.

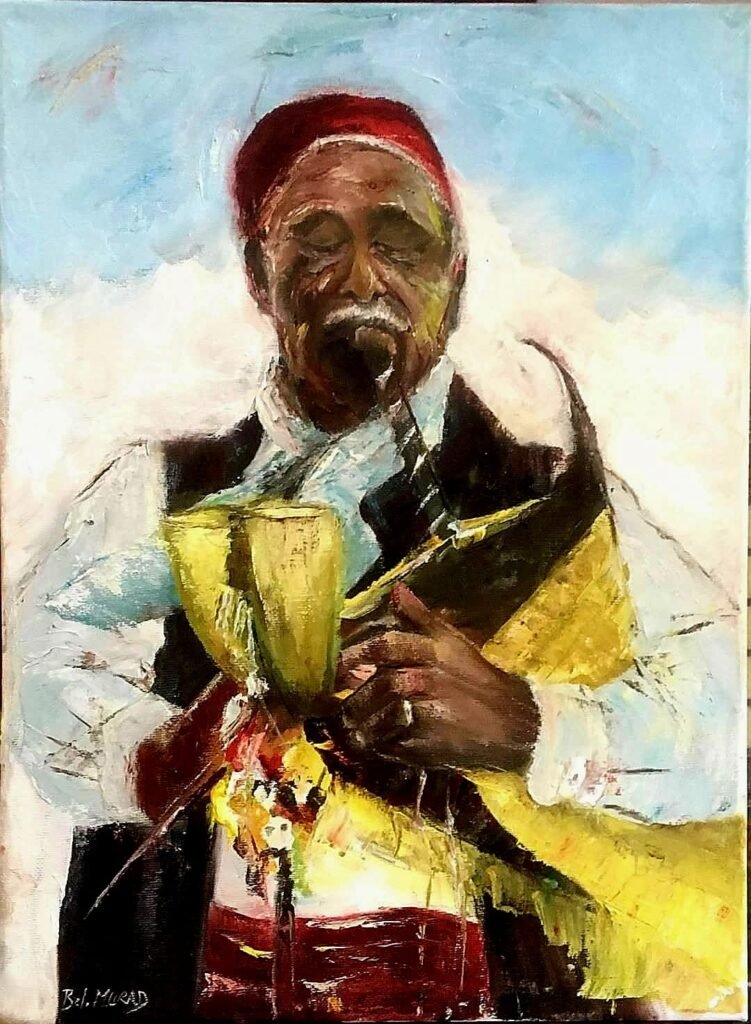

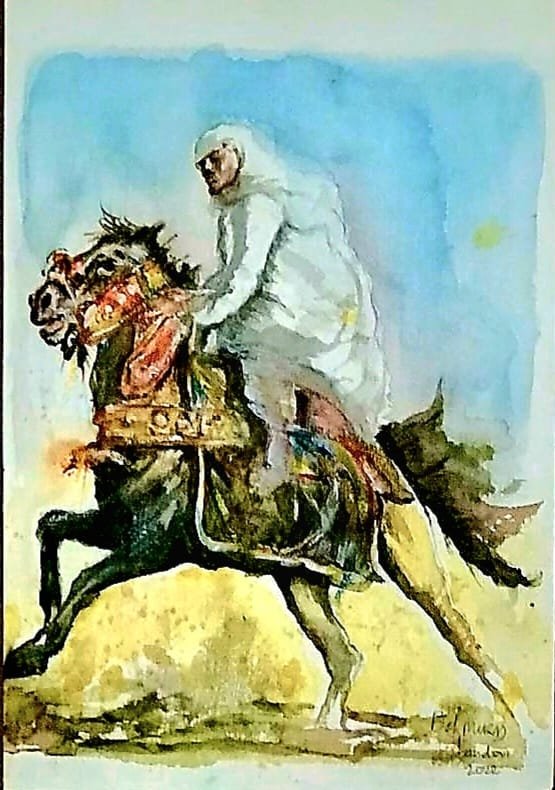

Belhaj, born in Tripoli and raised between cultures, has built a body of work that draws from the textures of everyday life in the Old City. His watercolours and acrylics offer scenes both intimate and expansive – alleyways washed in warm light, children darting past ancient doorways, the worn elegance of an old mosque at dusk. But what gives his work depth is not only its subject, but its intention.

“I’m not trying to explain Libya”, he says. “I’m trying to observe it, to hold onto something before it fades”.

That impulse – to hold, to preserve – is at the heart of much of Libya’s artistic practice, past and present. With few formal institutions and little market infrastructure, Libyan art has long existed in a fragmented space, passed between private homes, informal exhibitions, and occasional international appearances. And yet, despite the absence of systems, the creative instinct has endured.

Libya’s visual culture is layered, shaped by its Mediterranean geography, Islamic traditions, Amazigh roots, Ottoman and Italian influences, and more recently, post-colonial statecraft. From the geometric rhythms of desert architecture to the fluid lines of calligraphy and the vibrant motifs of Tuareg ornament, Libya’s aesthetic language is rich – but rarely decoded.

“It’s not that we don’t have an artistic tradition”, Belhaj notes. “We’ve just never framed it as such. What in other countries is called design or heritage, here it’s just daily life”.

Indeed, much of Libya’s visual identity lives outside the gallery – in ceramics, textiles, jewellery, and architecture. The artistic act, in many cases, has been anonymous, collective, and practical. In the absence of a robust national arts infrastructure, personal expression has often been subsumed into craft. Even now, many painters and sculptors work with little visibility or support.

The reasons are complex. While some periods saw investment in cultural production, others prioritised unity over diversity, tradition over experimentation. For years, artistic platforms were limited and tightly controlled. Themes of identity, abstraction, or critique found little room to breathe. Yet the effect was not silence – rather, redirection. Artists adapted, shifting their focus to memory, metaphor, and space.

Belhaj’s paintings belong to that lineage. His brushwork is restrained, almost reverent, with a palette that suggests both nostalgia and continuity. The Old City of Tripoli – medina walls crumbling under salt air, light filtered through mashrabiya screens – is more than a motif. It becomes a repository of collective memory, a site of resistance against forgetting.

“What interests me is not just place, but what it holds”, he says. “Smells, sounds, the way people greet each other, the things that disappear without us noticing”.

He speaks slowly, choosing words like a painter chooses tones. There is a quiet intensity in his vision – not dramatic, but deliberate. Libya, he insists, has something to offer the world artistically, but also something to regain internally.

“People often ask where the Libyan art scene is”, he says. “But the real question is – what counts as art? If we wait for institutions to validate it, we’ll be waiting forever. What matters is that it’s happening”.

That it is happening is beyond doubt. Across Tripoli, Benghazi, and Sebha, younger artists are working with murals, digital media, photography, and street performance. Some draw from heritage, others challenge it. Many operate informally, supported by community rather than commission. Online platforms have opened new audiences – yet questions of sustainability remain.

“There’s so much talent”, Belhaj says, “but so little infrastructure. We need archives, residencies, studios. We need critics. Not to judge, but to make sense of what we’re seeing”.

Asked what he hopes for the future, he offers no manifesto – only an idea. That Libya might one day have a space for its artists not defined by crisis or exile, but by presence. That its art might be seen not as a curiosity, but as part of the world’s ongoing cultural conversation.

“Libya doesn’t need to explain itself”, he says. “It just needs to be visible”.

And in Belhaj’s paintings, it is – quiet, luminous, and unafraid to remember.